A former karate instructor, Zlatko Keskovski is way ahead of them. At his facilities, workers dressed in medical drabs tend to flowers grown under fluorescent lights, carefully tracking and documenting production and storage.

It may be one of the more unusual economic models, but the two men are part of a plan to turn the former Yugoslav republic now called North Macedonia into a nation of cannabis farmers.

It’s early days, but the aim is to get a piece of a global medical marijuana market that’s predicted to reach anything between $14 billion and $50 billion over the next five years. And whether it’s former policemen, a lawyer or relatives of the prime minister, everyone seems to want in on it.

More than two dozen companies have been licensed since 2016 and the Health Ministry is processing another 20 applications, all in a place just slightly larger than Vermont and with a population of about 2 million people.

“We think it will be a lucrative business,” says Sevdinski, 49, surrounded by empty buckets at his premises in the city of Kumanovo, about 40 kilometers northeast of the capital, Skopje. He and his partner have spent 700,000 euros so far and will spend the same again to get the business going. “In about a year and a half we expect to be profitable,” he says.

The question is whether such ambition is matched by reality in a country that’s been in the global spotlight most recently for a cottage industry of fake news websites, some of which became notorious in the 2016 presidential election in the U.S.

The economy since the breakup of Yugoslavia has been dependent on exporting tobacco, fruit and vegetables and auto parts. There’s still no legislation to allow most exports of medical cannabis, though it has cross-party political support and the government says it wants to pass it in coming weeks.

There’s also the issue of corruption. The Balkan region is already a transit route for illegal drugs and the concern is the weed might just end up on the black market, especially without a legal outlet for the developing industry. Transparency International places North Macedonia 93rd in its Corruption Perceptions Index, level with Kosovo next door, Panama and Mongolia.

Prime Minister Zoran Zaev is behind the push as North Macedonia tries to forge its way in the global marketplace and even join the European Union after finally resolving a political dispute with neighboring Greece over its name last year. The nation is among Europe’s poorest, with average monthly salaries of $450.

“If we want to raise economy in North Macedonia, cannabis is the way to boost it,” Health Care Minister Venko Filipche says.

At the moment, the law doesn’t allow weed growers to do what they all need to make money: export the dry flower. Licensed companies are allowed to grow medical cannabis and extract oil, which can be exported. Yet only a small fraction of them actually extracts oil.

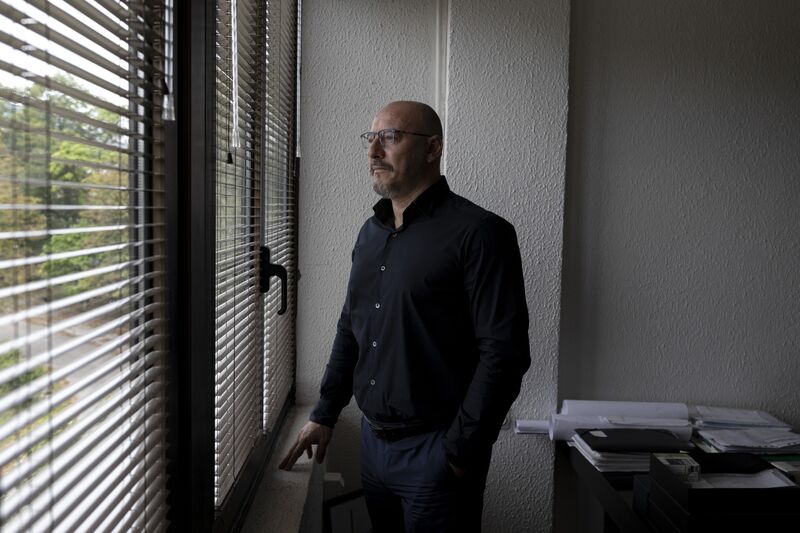

Keskovski’s company, NYSK Holdings, is based in Skopje and was the first to obtain a license. The former head of the president’s security detail, he says the dream of becoming a hub for growing cannabis depends on pushing through the legislation to allow exports, and the problem is the government appears to have lost momentum.

“If this law isn’t passed, this industry will be dead,” says the 49-year-old, sitting in his cigarette smoke-filled office with a shelf displaying half-full whiskey bottles. He’s confident, though, his business will survive regardless.

Indeed, the activity at NYSK is a stark contrast to others. On a tour of the country last month, most Macedonian growers appear to be mainly storing the dry flower, hoping the long-promised fix to the legislation will soon let them export it. That’s if they managed to produce anything.

One of the prime minister’s cousins, Trajce Zaev, has set up a 22,000 square-meter cultivation facility near the town of Sveti Nikole. It was initially designed to grow tomatoes, a source of pride for the prime minister when he meets other leaders.

Last month, the sprawling unmarked greenhouse, surrounded by barbed wire and patrolled by four security guards, was empty of cannabis. Trajce Zaev declined to discuss his business when contacted by phone and e-mail.

The problem, as ever, for such a fledgling industry is money, according to Kostadin Dukovski, who heads a five-month-old association of cannabis growers. The government is trying to tax it before it’s been allowed to get off the ground, while many newcomers just don’t have the investment or know-how, he says.

“They think that with cheap money they can do something big,” says Dukovski, who used to run a security department in the interior ministry. “But serious investment is needed to make it work. The problem is not to become big, the problem is what to do with the product.”

The risk is that it then could be sold illegally, he says. The current stock of dry flower and oil ready for export stands roughly at 60 million euros, Dukovski’s association estimates.

One man who does have the money to match his ambition is Slave Ivanovski, a millionaire who made his fortune from the natural gas trade in the Balkans, construction and food industry. After 16 years of being one of North Macedonia’s biggest vegetable and lamb exporters, he’s switched to medical cannabis.

His investment so far runs into the dozens of millions of euros since 2017, says Ivanovski. His company, Oaza Alkaloidi, employs 45 people at a new unmarked facility near the village of Tarintsi. A bust of Alexander the Great, the leader of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon whose heritage was at the core of the dispute with Greece, decorates his office.

“We did this actually also to help our state as it doesn’t have any ways to make money,” says Ivanovski, 59. “I’ll soon get the money back. This is the best business in the world.”